|

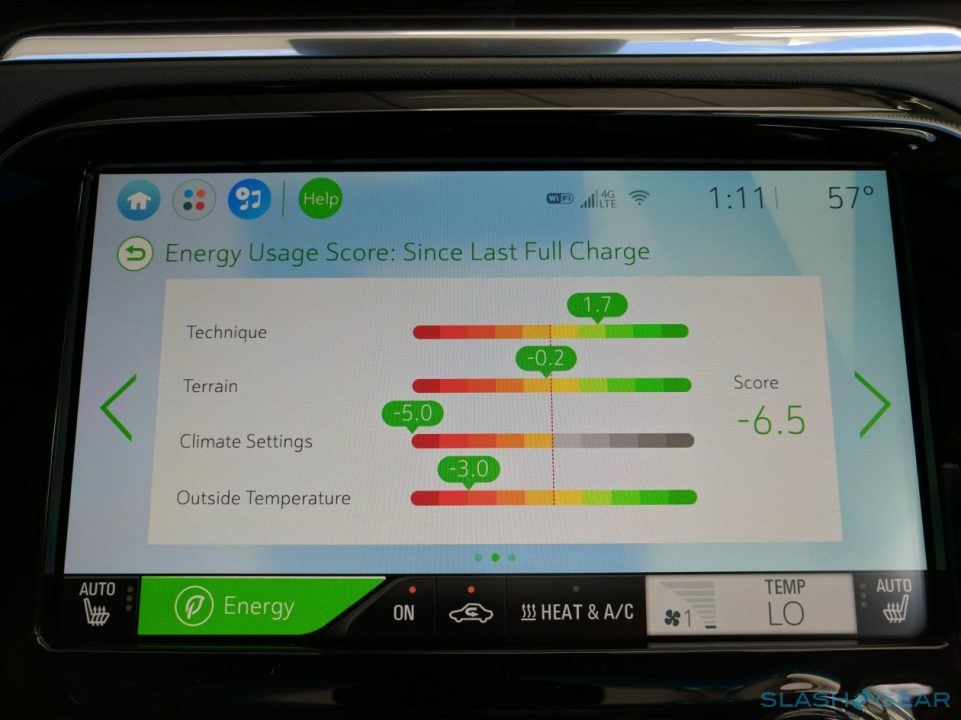

Nearly two years ago, I wrote a blog post on this site about why we were not buying an electric car. I’m happy (overjoyed, actually) to report that patience pays off. We are the proud new owners of a shiny new 2017 Chevy Bolt EV (Electric Vehicle). How did this come to pass? A big factor was this particular car. The Chevy Bolt just became available a few months ago in California and Oregon, and will go nationwide in the fall. It won Motor Trends’ Car of the Year award. It advertises 238 miles per charge (we’ve gotten to 305) – no more range anxiety. It’s roomy inside for my 6’4” husband, and the kids can sit in back without their knees being crushed. I can fit an entire Costco load into the (hatch) back. It’s peppy, smooth and whisper-quiet. It’s fun to drive – its road performance has been favorably compared to the Tesla. It has a digital dashboard 10” touch screen that can display your smart phone screen. Another screen feeds you all info about your energy use (makes sense – this is likely why you bought it), including a rating of your driving technique for maximizing energy output. The rating system is impacting how I drive, to a near-obsessive level. “2.6? What the heck? Did I get docked for accelerating too quickly? How is my husband getting to 2.9?” rom the minute we got the Bolt home, we could charge it by plugging it into a regular electrical outlet. It gains about 6 miles for every hour of charging that way. Once we install a charging station, it’ll gain 25 miles/hour. We can program it to charge only when electricity rates are lowest. After $7,500 federal tax credit and $2,500 state rebate, and the $500 from the utility, the price tag is around $30,000. The car is not pretentious, but it’s not ugly. And unlike the Tesla Model 3, its closest EV competitor which may not be out for another year or so, it’s available right here right now. But does this car meet the conditions I outlined in my 2015 post under which it would make sense to buy an EV? Let’s check. They were:

Taking these in order: Old car: In the last two years, one of our cars has made several trips to the repair shop. There’s nothing wrong with it; it’s just reached the age that various parts need repair or replacement. In reality, it’s got a lot of life still in it. However, I have chosen to characterize each shop visit as an augur of impending doom – a sure sign that we have driven is “into the ground”. I say, “You see, Honey? This thing is falling apart. Completely unreliable. It’s headed to the junk heap any day now. Probably time to get an electric car.” I call it Raising the Subject. My husband calls it Drip Water Torture. In any event, it seems to have hastened the 12-step process of getting to acceptance of EV ownership. (See “Emotions” bullet below.) Car manufacturing emissions: The Chevy Bolt’s Orion Assembly manufacturing plant is making manufacturing greener, with 54% of its energy currently coming from renewable sources (landfill gas). Chevy’s goal is to have 125 megawatts (MW) of renewable energy capacity by 2020, and it has committed to using 100% renewable electricity across its global operations by 2050. Other EVs are also being manufactured in cleaner, greener ways. For instance, much of the plastic, aluminum and CFRP (carbon fiber reinforced plastic) in the BMW i3 is recycled, saving energy on extracting and processing raw materials. And the i3 carbon fiber and production plants operate on 100% renewable electricity. Battery manufacturing emissions: The manufacturing of the batteries is not particularly emissions intensive, but to be fair, the extraction process still can be. Some types of EV batteries (and batteries for cell phones and other electronic devices) require mining of rare earth minerals such as nickel and cobalt, with which there are problems with sustainable and ethical sourcing. For instance, at one mine in China, the extraction process involves toxic chemicals. Only 0.2% of what’s extracted is rare earth minerals. The rest is returned to the environment, now contaminated with the chemicals. And a cobalt mine in the Congo has some pretty awful working conditions. The lithium ion that makes up the bulk of batteries is recyclable, but it’s currently so cheap that there’s no financial incentive to do so. Hopefully as EVs become more common, the rare mineral sourcing problems can be addressed with appropriate regulations and supply-chain standards. Further exploration may uncover additional sources of these minerals – possibly in the US. Even if not, the increased volume of EV sales may make recycling of batteries and their components more economically attractive (and provide American jobs and decrease reliance on other countries). Until then, landfilling of EV batteries can be delayed by re-using them in energy storage systems. Also, battery technology is evolving at a rapid pace, and the search is on for batteries that will run on more widely available materials. All in all, I feel confident that EV battery issues will never outweigh the environmental benefits of EVs. Bonus: Electricity emissions: Thanks to recent developments, it’s not just the manufacturing emissions for our EV that are lower. We’ve also eliminated emissions from generating the electricity to power the car. As you probably know, electricity is a secondary source of energy. It can come from burning fossil fuels like coal and natural gas, or from renewable, emissions-free sources like solar and wind. Last year, my county formed a CCA (Community Choice Aggregation) to procure electricity. The utility (PG&E) still maintains the power lines, delivers the electricity, and does the billing. But the CCA provides the electricity generation, with a cleaner default mix (50% renewable) than PG&E’s mix (30% renewable). We opted up to 100% clean electricity at a small premium over the PG&E rates. This costs us about $3 extra/month, and it means we charge our car at home with our electricity dollars going toward 100% renewable, greenhouse gas free sources. (Because of shade trees, our home is not suited to rooftop solar – otherwise, that would have been another option for clean electricity.) Battery Life: The Bolt’s warranty is for 8 years or 100,000 miles, which is now fairly standard among EVs. Automotive insiders say there’s no reason they can’t last 150,000 miles or more. It took us about 14 years to cover 100,000 miles in our old cars, so I’m betting we’ll be driving our Bolt at least that long. Also in our favor is Northern California’s near perfect year round 60 to 70’ish temperatures, which batteries tend to like better than extreme heat or cold. Emotions: As mentioned above, my constant raising of the subject of how great it would be to have an EV surprisingly seems to have had a wearing-down effect. I believe my husband was absolutely right to consider all the factors I mentioned over (and over and over) and come around to the inevitable conclusion that all conditions were satisfied for our switch to electric. He understands well, due to the power of repetition, that I think buying an EV is important because it drives demand for EVs, which leads to more and better EVs hitting the market. He loves the car; I do too; we love each other and the environment. Happy ending! But what does all this mean for you, dear reader? Should you, too, experience the joys of EV ownership? Here’s my advice:

The holidays are here. And so is the warmest year on record by a long shot, bringing with it more threats of unprecedented storms and other weather-related disasters. To ensure plenty of Holidays Yet to Come for ourselves, our children and future generations, we need to make merry in ways that are friendly to our Tiny Tim of a planet. Don’t worry – it’s not that hard to do. Come along; let me show you….

Celebrating: You can have a rip-roaring celebration without trashing the planet. And it’ll likely be cheaper, too. Here’s how:

Gifts: With gifts, it’s the thought that counts -- but not just a thought about the recipient, or meeting a social obligation. The thought that counts is a thought about the recipient’s children and grandchildren, and the planet we will leave to them. Physical gifts can be fabulous if they’re something the recipient really wanted and will use for many years. But usually they’re not. And if you need scissors or power tools to rescue the gift from the bomb-proof casing around it, that’s a sign it has too much packaging. We live on a finite planet. Here are some downsides of physical gifts and the packaging they come in. Such gifts usually involve:

And a lot of atmosphere-warming carbon dioxide is emitted in:

You’re probably thinking, “But we live in a capitalist society. It’s my obligation as a good capitalist to support the economy by buying stuff – especially stuff that doesn’t last long. Viva la stuff!” The good news is, you don’t have to choose between the economy and the environment. Two options that will continue to fuel the fire of the economy:

As Tiny Tim would say, “God bless us every one!” Last week we went to our kids’ back-to-school picnic. It was a beautiful event, except for one thing: 700 single-use plastic water bottles – a donation from a well-meaning real estate agent. At the end of the evening, the tables were littered with these bottles. Many of them were full but for a few sips.

I noticed another parent emptying the bottles on the parched shrubs and putting them in the recycling bin. Good for the shrubs, I guess. But other folks were tossing the bottles into the trash, which of course is headed to the landfill and oceans – where they are wreaking havoc with our environment and health. The Huffington Post reports that the US consumes 30 billion disposable water bottles per year -- 60% of the world’s total, even though we are less than 5% of the population. It takes about 17 million barrels of oil to produce those bottles – enough to fuel 1 million cars a year. In recognition of the environmental impact, more than 60 universities in the US and Canada have banned disposable water bottles on their campuses. According to Business Insider, bottled water is no safer or cleaner than tap water, and (surprise!) about half of all bottled water is derived from tap water. In blind taste tests, tap water consistently ranks at or above the level of bottled water. With certain exceptions, we don’t need, and shouldn’t use, disposable plastic water bottles. Back to the story: I spoke with the organizers of the back-to-school event, and they agreed that it was appalling to see all the unnecessary bottles. They also said it had been a real challenge to haul all that water to the event. In the end, we came up with several ideas for next year:

I left feeling better. These were middle schoolers, after all. A small subset of humanity. There was agreement that disposable bottles would not be at future school events. Problem solved, right? Not so fast. Just for fun, the next day as I was walking through downtown Menlo Park, I peeked into every recycling and trash bin (and there were many – usually with recycling and trash right next to each other, each clearly marked). Check out the photos I took of the trash bins, below. Without exception, every single trash bin had recycling in it. And sadly, some of the recycling bins had trash in them. At the risk of being marked as a dumpster diver, I started compulsively moving the items to their proper bin. When I got to items that were down lower than I could reach without risking toppling in (like when Lucy tried to fish a letter out of the public mailbox -- where was Ethel when I needed her?), I stopped. This was crazy. Why could not the good people of Menlo Park get it right? The next night, I went to a tailgater on the Stanford campus before the football game. These were Stanford students, parents and families -- generally a pretty smart lot. Again, bins clearly marked as “Recycling” or “Landfill” were readily available. And yet, the Landfill bins had plastic (and glass) bottles scattered throughout. I rolled up my sleeves, reached in and moved the offenders to their proper bin. If certain people saw me, my kids’ chances of admission were ruined. But I didn’t care. If Stanford people can’t recycle properly, who can? If this admittedly small set of data is representative, it appears that, at least in public, when it comes to recycling disposable plastic bottles, we Americans are ignorant, apathetic or both. In fact, the EPA reports that only about 30% of plastic water bottles get recycled. And even for those bottles that do get recycled, recycling takes a lot of energy. I’m convinced that if we want our planet to remain habitable, safe and beautiful, we’ve got to break the single-use plastic bottle habit. The change has to start with me. Here’s my list of goals, in order from easiest to hardest:

Below: Recycling bins -- clearly marked, on every block in downtown Menlo Park -- and the recycling that was in every single one of them.  I recently told my mother in law that I had given up red meat. “For dietary reasons, or humanitarian ones?” she asked. “Neither,” I responded, “For the environment.” She gave me a puzzled look. In my mind, there was no doubt: for the health of the planet, I must do my part to reduce the demand for beef. Depending on which source you consult, there are somewhere between 0.9 billion and 1.5 billion cows in the world. Cows are vegetarian, and, as vegetarians and those who love them know, being vegetarian makes you gassy. But beyond the antisocial nature of cow farts (and burps) lurks something much more evil. Its name is methane, and its symbol is CH4. In addition to being smelly, methane also traps radiation very efficiently. Compared to CO2, pound for pound methane’s impact on climate change is 25 times greater than the same amount of CO2. According to the EPA, globally the agriculture sector is the primary source of CH4 emissions. And it’s not just cows. Sheep, goats, buffalo, and – you guessed it -- camels -- produce large amounts of CH4 as part of their normal digestive process. One article explains that a single cow can produce 66 to 132 gallons of methane a day. Compare this to the average US vehicle gas tank, which holds 16 gallons of gas. A gallon of fuel in a car produces about 1200 gallons of CO2 at standard temperature and pressure. So a cow producing 100 gallons of methane (at 25x more harmful than CO2 to the atmosphere) a day is like using about 2.5 gallons of gas per day. If the average car gets 30 mpg, the emissions from one cow are as harmful as a car driving 75 miles a day. A billion cows is like a billion extra cars each driving 75 miles a day. It’s no big surprise, then, that a report by the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization found that the livestock sector “generates more greenhouse gas emissions as measured in CO2 equivalent – 18 percent – than transport.” To be clear: raising cattle hurts the atmosphere more than driving cars. The report also calls the livestock sector “a major source of land and water degradation.” Turns out livestock use 30 percent of the earth’s entire land surface. And supporting all those cows is a major driver of deforestation. In Latin America, 70 percent of Amazon forests have been turned over to grazing. Americans consume more than 37 million tons of meat each year. According to the National Chicken Council (are they competitors?) we Americans eat 54 pounds of beef per year, per person. That's the average. Obviously some folks are on the way high end of that scale, such as those who take on the 72-oz steak challenge offered in my home state of Texas. That also puts the USA at #5 in per capita beef consumption, behind Hong Kong, Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil. China’s per capita average is just 7 pounds per year. What about other types of meat? Beef beats them, hooves down, when it comes to environmental harm. Research suggests that beef does ten times more eco-damage than other kinds of meat. So, what can you do? If possible, give up beef and dairy products altogether. If you can’t do that, at least cut back. Meatless Mondays is a good start. Beef-free BBQs. Fro-yo-No-No Fridays. Steakless Saturdays, etc. Me? I’m committing to living a life free of cattle products from now on. (Ack! I guess that includes leather.) Thanks to lactose intolerance, I’m off to a good start.  A couple of weeks ago I flew from San Francisco to Denver on Frontier Airlines. Because I’m in my “ecodecade” – ten years I’ve committed to having the biggest net positive impact on the environment – I was looking for anything green to compensate for all the CO2 emitted by the jet fuel. I felt pretty good about bringing my own reusable water bottle on the plane. Frontier’s business model is to charge separately for everything but the forward motion of the plane – including bottled water and all other beverages. So the choice was pretty easy. But I was looking for more. When the flight attendant passed by with a bag to collect trash, I asked if the trash would be separated and recycled. Attendant: No. I: Why not? She: Because there’s not room on the plane for that. I: But you don’t need any extra room. You have room on the plane for the trash itself. Recycling just means you would separate out the recyclable stuff. Then you’d walk off the plane in Denver and put it in the recycling bins right inside the terminal. She: Um, we don’t do that. I: Ok then, I’ll just keep my trash and recycle it myself. When the passenger behind me started to give the attendant his newspaper, I turned around and said, “I’d be happy to take that off the plane for you. This airline doesn’t recycle.” A bit overboard, perhaps. But I felt like I was making a difference. When I got off the plane I went to the airline counter and asked why Frontier doesn’t recycle. The attendant nodded with a knowing smile. “I know. I’m big on recycling too,” she said. “We asked about it at the March meeting, and were told no. But we’re going to keep asking.” “Would it help if I wrote to the airline?” I asked. “Absolutely!” she replied. On the flight back home on Frontier, I asked the flight attendant if I might collect everyone’s trash myself in one of the airlines plastic bags, then sort and recycle at SFO – speaking just a bit loudly so other passengers could hear. Surprisingly, he was not up for letting me do this important work. The following week, I had to fly to Denver again for work – this time flying United. The CO2 guilt was killing me. Two flights in two weeks! I felt better after reading the “Eco-skies” page of United’s website, where Recycling and responsibly managing waste is listed as one of United’s sustainability initiatives:

27 million certainly looks like a big number. But how does it compare to the total pounds of recyclable waste generated? Apparently, not well. This report from 2010 ranked United next to last of 11 airlines for on-board recycling programs. On the United flight, I found not only failure to recycle, but also a bizarre sort of denial about it: Attendant: Trash, trash. Do you have any trash, miss? I: Do you recycle? She: Oh yes. We do recycle. I: But you’re collecting all the trash in one bag. Are you going to separate it when you get to the back of the plane? She (hesitates): Oh – THIS trash. No. We’re not recycling THIS trash. What the ??? Afterwards I wrote a letter to United, too. No response yet. Of course, there are other ways airlines can be eco-friendly, from reducing carbon emissions to sustainable design elements to green procurement to recycling aircraft parts to greening corporate offices. And oddly, this article from 2013 hails United as the “greenest” airlines in the world. The analysis is complex. But what to do about on-board recycling, at least, is simple. You, and I, and every person who boards a plane, just needs to ask this one question of every flight attendant: Do you recycle? Hey, kids! If you’re up for some good-natured, eco-fun, I highly recommend bringing a large garbage bag on your next flight. If there’s no recycling, wander the aisles collecting the can and newspapers yourself. It’s a hilarious prank that will leave a lasting impression on everyone on the flight. Let me know how it goes! I was on a flight recently, thereby increasing my carbon footprint by untold tons of CO2. The flight attendant collected my third plastic cup of the flight, in a bag that obviously was not headed towards a recycling facility. My eco-feelings were not happy ones.

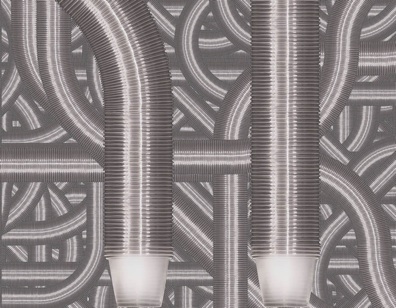

Afterwards, I poked around the Internet and found the haunting art piece shown above. What is it? It’s the one million disposable plastic cups used by airlines on flights in the U.S. every SIX HOURS. Unfortunately, that issue is still with us. But I found that a similar issue was solved by an online petition. United Airlines was using Styrofoam cups for its coffee. Dominique Kalata, a regular person from San Francisco, started an online petition to get United to switch to paper. With 13,461 supporters, she did. United announced they were switching to paper cups. Because it’s my decade of trying to make a positive difference for the environment, I decided to explore the broader question: Are online petitions for environmental causes worth signing? I will save you the suspense of reading further, and answer that question right now: Yes. Let me clarify: HELL yes. For those toying with the idea of making a positive eco-difference in the world, please know that this is one of the easiest, most effective things you can do. Especially if everyone does it. Especially if otherwise, you were going to do nothing. And especially if it leads to more awareness of eco-problems, more eco-funding, and more eco-activism, which studies show it is likely to do. AND – this is huge – they can be a teaching tool for your kids. That’s right. Your kids can sign online petitions. You can talk about a particular petition as a family. Dinnertime bonding? Yessiree Bob. Critical thinking? Absolutely. If your kids decide to sign a petition, they can then follow it as it gains support (or doesn’t). And hopefully, eventually, your kids can see that their signatures made a difference; that they helped do something great for the environment. Where else are you going to get a family opportunity like that? Because really, for the lazy/busy but environmentally concerned like myself, this is the choice: Option A:

Option B:

If you’re already convinced that online petitions are for you, stop reading this and go sign some! Hey. You’re still reading. You’re worried. Or afraid. I can see your brow furrowing (you should probably turn off your device’s camera). I know what you’re thinking. Let me allay your concerns. Concern: If I provide the info required to sign the petition, I’ll get a bunch of spam. Response: Create a new email account just for signing petitions. Do the same for your kids. I will say that I’ve been signing lots of environmental petitions the past few months. While I do get updates, other petition alerts, and requests to help fund campaigns, it’s clear these organizations have not sold my email address to anyone else. Concern: This will come back to haunt me somehow.

Concern: I may not understand all the nuances of this petition, and might end up petitioning for something I don’t really believe in. Response: Stick to those petitions created by organizations you trust to know what they’re talking about. The Nature Conservancy, Sierra Club, Greenpeace, World Wildlife Fund, Natural Resources Defense Council, Environmental Defense Fund, TerraPass.com, National Audubon Society – all these are longstanding, reputable organizations. If they’re behind a petition, you can be pretty sure it’s been carefully thought through. Concern: I’ll just be wasting those 5 minutes reading and signing an online petition, because I’m not sure if online petitions are effective. Response: Online petitions do work -- certainly to raise awareness. And sometimes to get the desired result – depending on a variety of factors. And they can result in further action, which may end up getting the desired result. In any event, the 5 minutes spent are well worth it. Read on. One way an online petition works is by raising awareness of causes and issues –

Even if the petition does not result in immediate action, the awareness it raises may prompt action down the road. In some cases there’s evidence that the online petition directly caused the desired change. For instance, a Gatorade spokesperson told The New York Times that an online campaign against its use of brominated vegetable oil—an ingredient sometimes used as a flame retardant—led the company to speed up its planned phase-out of the product. More often, it can’t be proved that the petition alone caused the change, although it likely played a role in bringing about the change along with other factors. See below for some examples. Online petitions also work in that they can inspire further advocacy. According to a Pew Research Center study in 2013, nearly one in five active users on social networks said information they learned online inspired them to take further action. And a study from Georgetown University found that those who engage in social issues online are twice as likely as their traditional counterparts to volunteer and participate in events. The success of an online petition also depends on how well it’s designed and executed. One of the biggest online petition websites, Change.org, lists the following features that make online petitions more likely to succeed:

Here are some examples of effective online petitions:

Let’s recap. Here’s what you should do:

And if by chance you decide to get even more involved – through social media, a donation or even starting your own petition, well, you can thank your start with online petitions. In the immortal words of Elle Woods, in the epic film Legally Blonde 2, “Speak up!”  The other day I was on a walk to the Stanford Shopping Center, and stopped in at a gourmet grocery called Sigona’s to buy a Snapple. Diet Peach, to be precise. Right then it hit me. Fossil fuels were burned to manufacture that Snapple bottle. Fossil fuels were burned to ship it to Sigona’s. Fossil fuels would even be burned even in the recycling of that bottle, and all the further transportation around that. Did I let this realization pass by, as a mere fleeting thought? No I did not. I acted on it. Well, I inacted on it. Instead of buying the Snapple, I did the environment a favor* and didn’t buy it. I engaged in environmental inactivism. Afterwards, I felt proud of myself. But then sad. I had nothing to show for my environmental inaction. I had nothing to boast about. “Hey, I didn’t buy a Snapple today. Isn’t that great?” Whatever. And if I said nothing, no one would even know. I thought about the fact that most of the stuff we extract, manufacture, produce, ship and even recycle requires the burning of fossil fuels, or using lots of water, or both. I thought about how quickly the human population is growing, and how ever more people are buying ever more stuff.** I also thought about how hard it can be to NOT do things. As anyone knows who has ever dieted, discovered a 50% off sale, observed Lent or Yom Kippur, possessed a credit card or been a teenager, restraint is difficult. And when it comes to the environment, it’s largely uncelebrated. And that made me think about all the environmental inactivists out there, making a huge difference for the planet. They are the unsung heroes of our time. For example, consider Elon Musk, CEO of Tesla Motors, who has overseen the production of more than 70,000 cars. A lot of fossil fuels were burned in manufacturing those cars, and a lot will be burned in generating the electricity to power them. Elon received the Environmental Media Association’s Corporate Responsibility Award. But his younger brother Kimbal opened some restaurants in Boulder. Elon has, no doubt, done a great thing, and deserves his award. But environmentally speaking, at least for now, Kimbal is way ahead of Elon. Kimbal has not manufactured even one car. Where is Kimbal Musk’s award? You don’t have to be related to a big name to engage in inactivism. Regular people are doing it every day. Here's an example of how environmental inactivism can show up in ordinary events:

Here's another:

Inactivism comes in many forms, some of which are hard to recognize. All these years, I misunderstood my husband’s behavior. He has actually been a strong environmental inactivist, reliably every year on my birthday and Valentine’s Day. The beauty of inactivism is, regardless of whether it’s intentional or accidental, it still helps the environment. We need to promote it and celebrate it. Don’t get me wrong. I’m not saying never do anything or buy any stuff. Often, doing things gives life meaning and keeps you active. Buying stuff (especially in the form of “shopping”) can be fun! And, you get to keep the stuff. Which oftentimes you actually need. Moreover, much of our economy depends on our buying stuff. That’s important too. So when you do things, or buy stuff, don’t feel guilty. Guilt, restraint, forbearance, self-denial – none of these things should be associated with helping the planet. That would not be sustainable. It’s that kind of framing that gives Greenies and Treehuggers a bad name. What I am saying is this:

As another example, my mother-in-law was attending a bat mitzvah, and complained that she had not bought a new dress for the occasion. I pointed out, “By not buying a new dress, you helped the environment.” I am certain it’s just a matter of time before she joins me in celebrating that one. And you? You should celebrate your inactivism. Even today. Because if you biked or bused to work, great! But even if you drove to work, you probably didn’t drive an 18-wheeler to work. And I’m guessing you didn’t drive across the country to work. Celebrate! If you didn’t use a single sheet of paper all day, yea for you. But even if you did use paper, you can probably say that you have never engaged in rainforest logging. You get the idea. So start celebrating your own environmental inactivism, and congratulating others on theirs. Say it loud, say it proud. If your audience is unreceptive to whatever you didn’t-do, tell me. I’ll make lots of hoopla around it. And I’ll keep records. Because someday, there will be an award ceremony bigger than the Oscars for environmental inactivism, and you’ll want to be in the running. *You might ask, “How is not-buying a Snapple helping the environment? The bottle was already made and shipped.” Good question. It helps because Sigona’s market is tracking how many Snapples are sold, and Snapple Headquarters is tracking how many Snapples are ordered. And if fewer are ordered, fewer will be made. So that’s how. Takes a while, but it comes around. **And why is that so bad? Because burning fossil fuels releases greenhouse gases. Earth’s rapidly growing human population is manufacturing and producing and transporting more stuff than ever before, burning staggering quantities of fossil fuels. To the point that greenhouse gases are accumulating in the atmosphere at unprecedented rates, which makes climate scientists fret over how toasty warm we can stand our planet.  Here I am, about 6 months into my eco-decade – 10 years I’m dedicating to having the biggest possible net positive impact on the environment. At this point in my exploration, about all I’ve discovered is that I’m an eco-hypocrite. I’m unwilling to give up all but the smallest conveniences and creature comforts for the sake of the habitability of the planet. Clothesline instead of a dryer? I don’t think so. So I need a big eco-win. And I thought I knew what it would be: a shiny new electric car. At first I had my sights set on a Prius – the quintessential hybrid, ubiquitous in these parts. But then I thought No. I’m going even one step FURTHER in the name of Mother Earth. Electric, my friends, all the way. 100%. My dream eco-car? The Nissan Leaf. Preferably in baby blue, the color the clear sky will be when I’ve rocked this eco-challenge. The Leaf is cute, and reasonably priced at about $30,000, minus the federal tax credit of $7500 and California’s $2500 rebate – so only $20,000 really. It gets about 80 miles per charge, which is plenty for our family’s around-town and carpooling needs. Our current cars both date back to the year 2000: a Lexus 300 SUV, which is averaging a painful 18 mpg, and a Volkswagen Golf, slightly better at about 30 mpg. I feel we are ready for a change. So imagine my shock when I raise the subject with my dear husband, and he says, “It’s better for the environment to keep driving our old cars.” WHAT??? What he says must be true, because my husband is always right. (He is right because of a deal we struck early in our relationship: He’s always right, and it’s always his fault. I later learned this was bad negotiating on my part. Many husbands only get the fault half of the deal. But I digress.) Sure enough, I start investigating, and guess what? A LOT of fossil fuels are burned to produce the energy to manufacture a car. According to The Guardian, around 6 to 35 tons of CO2 are emitted in the manufacture of a car. (The analysis is explained further here in metric and therefore largely incomprehensible.) Depending how many miles you drive the car over its lifetime, and how fuel-efficient it is, the manufacturing CO2 emissions may be around the SAME as the driving CO2 emissions. In other words, your total emissions-per-mile-driven doubles when you take into account the manufacturing emissions. Let me put this another way, in case you’re having as much trouble as I did accepting this fact: The very manufacturing – the mere creation of your car -- generally produces about half of its carbon emissions. Before you have even driven it silently off the lot, you’ve spewed around 15 TONS of CO2 into the atmosphere. And you do have to take into account the manufacturing emissions, or you are just lying to yourself. Lying is bad. Even if it gets you the car you want. The emissions-per-mile goes down the more miles you drive the car. Getting 200,000 miles over the life of your car, rather than scrapping it at 100,000, can help cut the emissions-per-mile in half. So, Gerald said, better to keep our old cars, and drive them as long as possible. Yes, Gerald is right, but I am not willing to let go of my dream that easily. Isn’t it just a question of who’s driving the gas-guzzler? I ask. If we sell our old car, it’s still getting driven for its natural life – just by someone else. That someone else (let’s call him Mr. X) would have bought a used car anyway. (That’s just the kind of guy he is.) And to buy OUR car, Mr X is selling HIS car to someone else who was going to buy a used car anyway. So all the cars are still being driven by someone for as long as they function. Only the drivers’ names are changing. So we still have the same number of cars in the world, right? I sit back smugly. I’ve got this. Nope. By buying a new car, we create the demand to manufacture that new car. Gerald is kind enough to explain with this example:

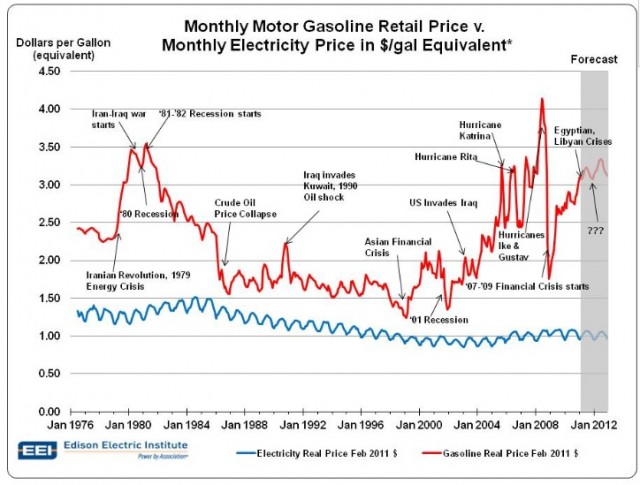

By keeping your car longer, you’re doing more good for the environment than you would EVEN if you always bought electric cars. Wait, I say in a last desperate attempt. But if we buy an electric car, the only emissions are the manufacturing emissions. The car does not even have an exhaust pipe. So with a new electric car, with every mile we drive, we are diminishing its emissions-per-mile. At this rate, surely the electric car will surpass a gas guzzler in eco-benefits in no time. Turns out this, too, is not a great argument. For one thing, even electric cars require energy to operate: Electricity. A few cities now get all their electricity from sources free of CO2, like solar and wind, but most cities still get their electricity from burning fossil fuels (including coal), or at best from a mix of renewable and fossil fuels. Our energy supplier, PG&E, gets around 20% of its energy from renewable sources. For another thing, electric cars operate on batteries, which don’t yet last all that long. For instance, the lithium ion battery of the Tesla Roadster is only good for about 5 years or 100,000 miles. And, as I know from my cell phone and camera, batteries degrade over time. It’s just not clear at this early stage how long electric car batteries will last. New batteries cost – you guessed it – well, yes, a lot of money -- but also lots of CO2 emissions to extract and fabricate the materials, and produce and install in the car. Net net, we already have our old cars. The manufacturing emissions already happened. We’re right in the middle of lowering our emissions-per-mile. So it makes the most environmental sense to keep driving them. Dammit. Under what conditions would it be eco-better to buy an electric car?

Until then, I think I’ll look into leasing.  Dear President Obama, If you really want to secure your place as the Environmental President, you have got to do something about the White House. Walk the walk! Send a message. Everything speaks when you’re the leader of the free world. So start in your own back yard. You’re still in there for a while yet. You get to decide this – Congress can’t hold you back. For starters, solar panels. I understand you put a token few on the White House roof, but how about more – lots more? Enough to actually power the whole W.H. And some panels on the White House lawn, too. That’s a lot of land – make it productive; make it green. You could have a virtual solar farm going there if you tried. If you replaced all that chemical- and water-guzzling lawn with tasteful dryscaping and solar panels, it’d help conserve water, too. And your motorcade? Demand that every single vehicle be electric. What a statement that would make! Not sure if it’s even possible for Air Force One to operate without fossil fuels. But if anyone can make it happen, it's you! At least ask, and see what happens. And how about tricking out the White House to be more energy efficient? Run a check – drafts coming in under any of the 412 doors? Are all 147 windows double-paned? When no one’s in a particular one of the 132 rooms, do the heating/AC and lights automatically go off? Do the 35 bathrooms have low flow showers and toilets? Are all the lights LED? In the White House kitchen? You could insist on biodegradable utensils and compostable plates. Prohibit plastic water bottles and soda cans. Compost the heck out of everything. And make the guests take only as much as they can eat. People are starving all over the world. Let’s set a good example, Mr. Prez. Regarding White House laundry – as folks in just about everywhere else in the world well know, dryers use a LOT of energy. Replace them with drying racks and clothes lines – the paparazzi would go crazy dissecting every item of laundry it could photograph. Make a big honking deal about doing all of this. Then challenge all the leaders of the world to do the same. Angela Merkel will be all over that plan. She’ll be jealous she didn’t think of it first. Then make every member of your Cabinet do the same for their homes and offices. Challenge Congress to green up, too. Not all of them will do it, but there will be a lot of press around this. Even if you don’t believe in climate change, diversifying energy sources is hard to oppose. And there’s no harm in using some renewable sources of power here and there. Then extend your challenge to every business leader, every billionaire, every member of the 1%. Make it a contest. Heck, even give out some prizes. You can do this! Yes you can.  Update 3/20/15: It's working! We're getting almost no junk mail now. Check it out! In about 15 minutes, you can stop that annoying junk mail and feel good about your climate action. Click these 4 links to stop your junk mail for free:

When I first posted my blog on Facebook, my dear brother commented, “If we could just stop junk mail alone…”

Made me think. How bad is junk mail for the environment, anyway? Aren’t I neutralizing any toll on the environment by recycling it? Turns out a lot of natural resources go into making a sheet of paper. I already knew the death of a tree was involved. One article from BizJournals.com says a ton of catalog paper uses nearly 8 trees. Heck, I’m pretty sure I get that much from IKEA and Room & Board alone. And here are some more stats on junk mail from NYU Law School:

The NYU article has a couple of typos, and cites to About.com and Creative Citizen as support, so I’m not sure how reliable it is. (Come on, NYU! I would have expected more out of you.) But even if it’s only partly right, that still a lot of environmental harm. So can we undo that harm by recycling? No doubt, recycling is better than not recycling. According to the Natural Resources Defense Council, studies are “virtually unanimous” in confirming that recycling saves energy. Recycling newsprint takes 40% less energy than virgin fiber use. The EPA states that recycling a ton of paper saves 7,000 gallons of water and reduces greenhouse gas emissions by 1 metric ton of carbon equivalent (whatever that means – more research to be done). But it’s still better for the environment not to make and distribute the junk mail in the first place. And here’s the punch line you’ve been waiting for… it’s pretty easy to stop the junk mail. Blessed by the Federal Trade Commission: If you trust the FTC, here are 2 ways to stop junk mail: 1. To stop pre-approved credit card and insurance offers: OptOutPreScreen.com. The form there looks scary in that it asks for your social security number. But on further investigation, I found that your SSN is not required. Whew. 2. To stop other mail: DMAChoice.org stops mailings “from organizations that use the Direct Marketing Association’s Mail Preference Service”. (Who knows which orgs those are, but hopefully they include Victoria’s Secret, from which I hardly ever buy, but which sends me mail about every 3 days. Vicky – do the math! You’re losing money on me.) Other sources: To stop junk mail: Hard as it may be to believe, a company called DirectMail.com has a free service to stop junk mail from companies that use DirectMail.com. Again, who knows which companies those are, but I’m willing to try it out for the sake of the planet. I checked it out and it looks legit – with the caveat that it may take 3 months to see the decline in junk mail. I signed up. I’ll keep you posted. To stop catalogs: CatalogChoice.org lets you pick off your catalogs one by one, by name. It’s not a one-hit fix like DMAChoice or DirectMail, but its lookup feature is pretty good. Plus, I just got a great deal of environmental satisfaction by stopping Victoria’s Secret just now. I’ll let you know how many days it took for the request to take effect. |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed