|

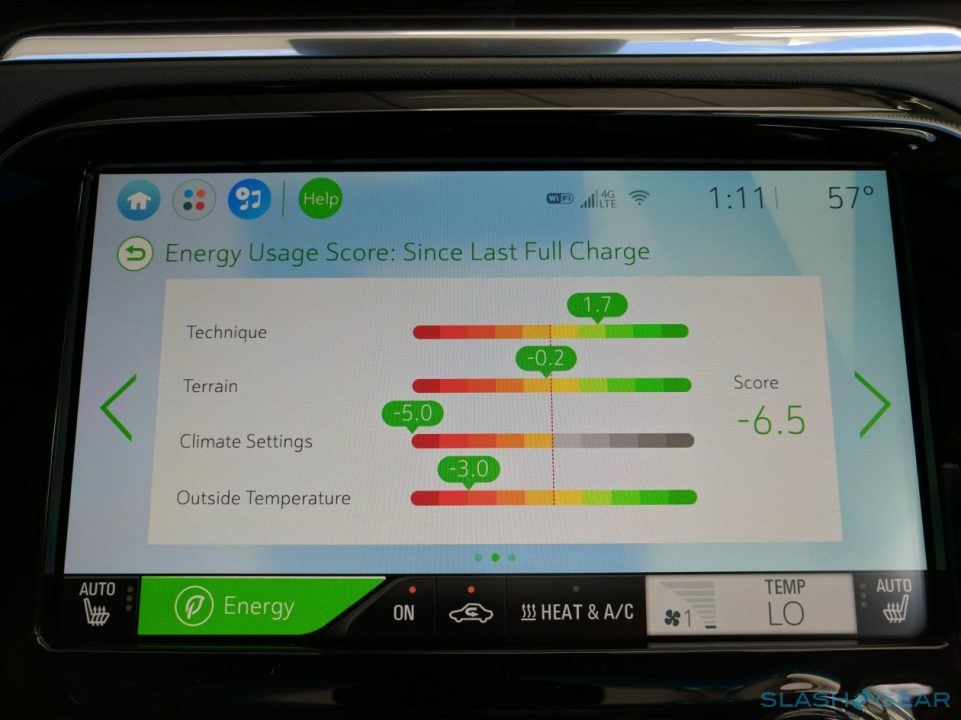

Nearly two years ago, I wrote a blog post on this site about why we were not buying an electric car. I’m happy (overjoyed, actually) to report that patience pays off. We are the proud new owners of a shiny new 2017 Chevy Bolt EV (Electric Vehicle). How did this come to pass? A big factor was this particular car. The Chevy Bolt just became available a few months ago in California and Oregon, and will go nationwide in the fall. It won Motor Trends’ Car of the Year award. It advertises 238 miles per charge (we’ve gotten to 305) – no more range anxiety. It’s roomy inside for my 6’4” husband, and the kids can sit in back without their knees being crushed. I can fit an entire Costco load into the (hatch) back. It’s peppy, smooth and whisper-quiet. It’s fun to drive – its road performance has been favorably compared to the Tesla. It has a digital dashboard 10” touch screen that can display your smart phone screen. Another screen feeds you all info about your energy use (makes sense – this is likely why you bought it), including a rating of your driving technique for maximizing energy output. The rating system is impacting how I drive, to a near-obsessive level. “2.6? What the heck? Did I get docked for accelerating too quickly? How is my husband getting to 2.9?” rom the minute we got the Bolt home, we could charge it by plugging it into a regular electrical outlet. It gains about 6 miles for every hour of charging that way. Once we install a charging station, it’ll gain 25 miles/hour. We can program it to charge only when electricity rates are lowest. After $7,500 federal tax credit and $2,500 state rebate, and the $500 from the utility, the price tag is around $30,000. The car is not pretentious, but it’s not ugly. And unlike the Tesla Model 3, its closest EV competitor which may not be out for another year or so, it’s available right here right now. But does this car meet the conditions I outlined in my 2015 post under which it would make sense to buy an EV? Let’s check. They were:

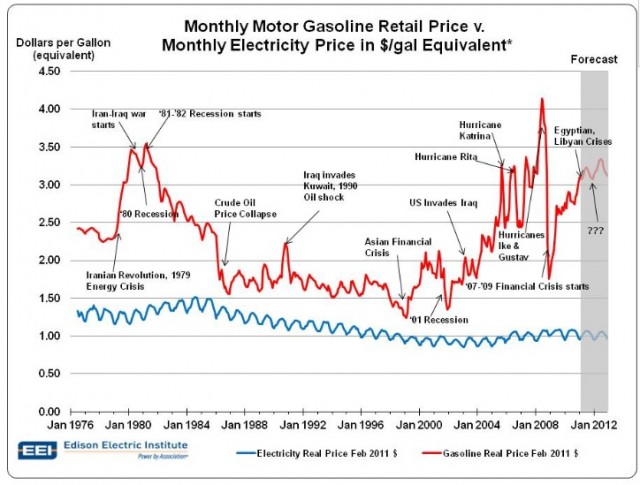

Taking these in order: Old car: In the last two years, one of our cars has made several trips to the repair shop. There’s nothing wrong with it; it’s just reached the age that various parts need repair or replacement. In reality, it’s got a lot of life still in it. However, I have chosen to characterize each shop visit as an augur of impending doom – a sure sign that we have driven is “into the ground”. I say, “You see, Honey? This thing is falling apart. Completely unreliable. It’s headed to the junk heap any day now. Probably time to get an electric car.” I call it Raising the Subject. My husband calls it Drip Water Torture. In any event, it seems to have hastened the 12-step process of getting to acceptance of EV ownership. (See “Emotions” bullet below.) Car manufacturing emissions: The Chevy Bolt’s Orion Assembly manufacturing plant is making manufacturing greener, with 54% of its energy currently coming from renewable sources (landfill gas). Chevy’s goal is to have 125 megawatts (MW) of renewable energy capacity by 2020, and it has committed to using 100% renewable electricity across its global operations by 2050. Other EVs are also being manufactured in cleaner, greener ways. For instance, much of the plastic, aluminum and CFRP (carbon fiber reinforced plastic) in the BMW i3 is recycled, saving energy on extracting and processing raw materials. And the i3 carbon fiber and production plants operate on 100% renewable electricity. Battery manufacturing emissions: The manufacturing of the batteries is not particularly emissions intensive, but to be fair, the extraction process still can be. Some types of EV batteries (and batteries for cell phones and other electronic devices) require mining of rare earth minerals such as nickel and cobalt, with which there are problems with sustainable and ethical sourcing. For instance, at one mine in China, the extraction process involves toxic chemicals. Only 0.2% of what’s extracted is rare earth minerals. The rest is returned to the environment, now contaminated with the chemicals. And a cobalt mine in the Congo has some pretty awful working conditions. The lithium ion that makes up the bulk of batteries is recyclable, but it’s currently so cheap that there’s no financial incentive to do so. Hopefully as EVs become more common, the rare mineral sourcing problems can be addressed with appropriate regulations and supply-chain standards. Further exploration may uncover additional sources of these minerals – possibly in the US. Even if not, the increased volume of EV sales may make recycling of batteries and their components more economically attractive (and provide American jobs and decrease reliance on other countries). Until then, landfilling of EV batteries can be delayed by re-using them in energy storage systems. Also, battery technology is evolving at a rapid pace, and the search is on for batteries that will run on more widely available materials. All in all, I feel confident that EV battery issues will never outweigh the environmental benefits of EVs. Bonus: Electricity emissions: Thanks to recent developments, it’s not just the manufacturing emissions for our EV that are lower. We’ve also eliminated emissions from generating the electricity to power the car. As you probably know, electricity is a secondary source of energy. It can come from burning fossil fuels like coal and natural gas, or from renewable, emissions-free sources like solar and wind. Last year, my county formed a CCA (Community Choice Aggregation) to procure electricity. The utility (PG&E) still maintains the power lines, delivers the electricity, and does the billing. But the CCA provides the electricity generation, with a cleaner default mix (50% renewable) than PG&E’s mix (30% renewable). We opted up to 100% clean electricity at a small premium over the PG&E rates. This costs us about $3 extra/month, and it means we charge our car at home with our electricity dollars going toward 100% renewable, greenhouse gas free sources. (Because of shade trees, our home is not suited to rooftop solar – otherwise, that would have been another option for clean electricity.) Battery Life: The Bolt’s warranty is for 8 years or 100,000 miles, which is now fairly standard among EVs. Automotive insiders say there’s no reason they can’t last 150,000 miles or more. It took us about 14 years to cover 100,000 miles in our old cars, so I’m betting we’ll be driving our Bolt at least that long. Also in our favor is Northern California’s near perfect year round 60 to 70’ish temperatures, which batteries tend to like better than extreme heat or cold. Emotions: As mentioned above, my constant raising of the subject of how great it would be to have an EV surprisingly seems to have had a wearing-down effect. I believe my husband was absolutely right to consider all the factors I mentioned over (and over and over) and come around to the inevitable conclusion that all conditions were satisfied for our switch to electric. He understands well, due to the power of repetition, that I think buying an EV is important because it drives demand for EVs, which leads to more and better EVs hitting the market. He loves the car; I do too; we love each other and the environment. Happy ending! But what does all this mean for you, dear reader? Should you, too, experience the joys of EV ownership? Here’s my advice:

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed